- Education Forums

Nave Mural Paintings, Trinity Church

(For the corresponding images, click here to download the PDF)

Trinity Church, Boston is widely considered to mark a turning point in both the architectural design and the interior decoration of American churches. Contemporaries praised the harmony of the color, the decorative details, and the figures. ( Weinberg, p. 353) Some saw the brilliantly colored and gilded interior, as having “Venetian splendor”. (Weinberg, p. 346 ) Others admired the painterly effect of the varied tones of the red walls themselves, pointing out how different this was from the mechanical patterns of the typical fresco decoration used by the housepainter-decorators. It was believed that this artistic approach, where the hand of the artist revealed a personality, rather than precise technical skill, was the reason for the greater unity between the figurative decoration and the architectural structure. ( Curran, pp. 715-716)

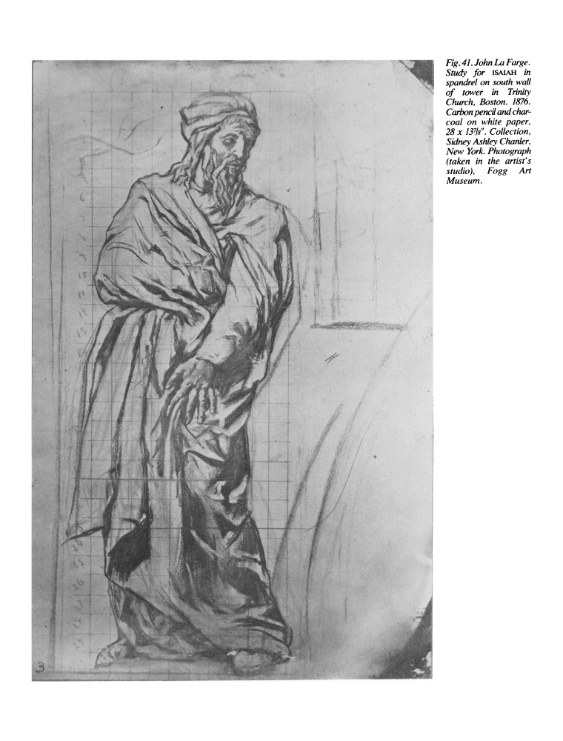

Although La Farge has rightly been considered as continuing the Renaissance workshop tradition where the assistants carry out the master’s style, he also continued the Renaissance artists’ experimentation with new technologies and materials. ( Mather, p. 247) This was La Farge’s first large-scale mural project, and he put together a team of younger artists-- ten years his junior-- with shared interests and a variety of requisite expertise, among them: Augustus Saint-Gaudens, who would continue to work on later projects with him, Francis Lathrop, who had studied in Dresden, and Frank Millet and George Maynard, who had both studied the Royal Academy of Art in Antwerp (Weinberg, p. 329) Francis Lathrop shared La Farge’s enthusiasm for the ideals and style of the Pre-Raphaelites and had worked in the studio of Ford Maddox Brown in England. ( Curran, p.716 ) While in Dresden, he had also studied fresco painting; and was considered to be La Farge’s “chief support”. This was especially in the early months when La Farge still worked from Newport. (Weinberg, p. 329) Lathrop would have had experience with applying large drawings or cartoons to walls and an understanding of how to distribute and pace the work, which began with the tower ceiling. Another important member of the team was Frank Millet, who was conversant with the new medium of photography. In a letter to Saint-Gaudens, La Farge mentions that, Millet was going to try to enlarge photographs of the small preparatory drawings with a magic lantern or projector onto a wall or rather paper. (Yarnall, p.15) This would eliminate the time required for the manual scaling up using a grid, which can be seen penciled in over some of the drawings for the tower. ( Illustration 1 ) Another technical expertise, which Millet brought to the project, was his knowledge of the encaustic technique that La Farge was planning to use for the interior. (Weinberg, Millet, p. 4)

As stipulated in the contract, La Farge was responsible not only for putting together a team of artists, but also for procuring the painting materials and finding decorative painters for the non-figurative sections of the walls. He was dismayed by the typical practice of decorative painters in distemper or fresco who, in order to keep up steady stream of work, used pigments which were not color fast. (Mather, pp. 249-50) La Farge may also have heard about the rapid deterioration of the fresco paintings completed by his mentor, William Morris Hunt, in 1875 for the Capitol in Albany. ( Crowninshield, p. 31 ) In contrast, the wax-based medium of encaustic although more expensive, was considered extremely water and moisture resistant. It was a technique that went back to the ancient Greeks and Romans, who had used it to decorate exterior architectural details, and for portraits of extremely vivid and luminous color. The technique was being revived on a large scale in France for the civic and religious buildings in the 1830s; (and the details of the technique were included in a comprehensive treatise on painting by Jacques-Nicholas Pailloit de Montabert’s: Traite complet de la peinture , 1828-29, which La Farge may have read ). La Farge does mention that during his trip to Europe in 1857 he had discussed the technique with Henry Le Strange, who had painted the ceiling of the west tower of Ely Cathedral using the technique. (Weinberg, p.330 ) While weather-proofing was likely to be an issue for the wall paintings, and especially for those in the tower at Trinity, La Farge’s insistence on a return to the high standards of materials and workmanship of the Middle Ages was also part of the Pre-Raphaelite aesthetic that critiqued the poor quality of most industrially produced home furnishings.

Given the importance of light and color to La Farge’s art, his choice of encaustic was also probably motivated by the characteristics of the wax-resin mixture to impart luster without the problematic glare of oil paint on canvas. Although La Farge had experimented with the encaustic technique in some small paintings, for the living room of Henry Marsh, ( wood engraver of La Farge’s illustrations ) ( Weinberg, p. 330) adapting the technique to the scale of the church must have been challenging. The modern encaustic technique was a cold process, which did not require the burning in or application of heat to mix and set the colors. It relied instead on a balsam resin, called Venice turpentine, to “melt” the wax.

(Hansen, p. 2 ) Then the wax-resin mixture was combined with spirits of turpentine and boiled. This mixture could be saved indefinitely; and it was to this mixture that the pigments could be added--by this time the newly invented tubed oil colors were available. The technique had the advantage of a quick drying time and did not produce cracks, which meant that subsequent layers could be painted as soon as the next day. In his 1887 treatise on mural painting, Boston artist, Frederic Crowninshield, included a section on encaustic method and explained both the ancient and modern techniques. He also gave a formula for the proportions of the wax-resin-turpentine mixture that he had found very workable and he credited the invention of the formula to Frank Millet. (Crowninshield, p. 38) Whether Millet’s formula was the result of his experience at Trinity Church is not mentioned. The addition of alcohol to this formula for the paint mentioned by Richardson, may reflect the need to keep the wax mixture from congealing during the frigid temperatures of the winter months when the church decoration was being completed. In normal conditions, there was a of the need to constantly adjust the consistency of the paint. Crowninshield recommended that the painter have two palettes with large cups with screw tops: one cup for the wax-resin medium and one for the spirits of turpentine. Another detail mentioned by Crowninshield, was that a studio boy was essential to clean the palette of the sticky colors to avoid what he called “foul mixtures”, that is neutral tones created by accidental mixing. ( Crowninsheild, p. 41) It is interesting that Richardson mentions that the team included such a studio boy, “the little boy of all work whose job it was to run the errands and stir the barrels of colors.” (Richardson, p. 65 )

Color and its relationship to the light within the space was the visual element that La Farge used to maximum decorative effect. As one enters the church one is immediately struck by the bold contrast of the azure blue figures of the apostles, Peter and Paul, against the vermillion orange background of the tower. The brilliance of the color contrast is increased by the reflections and highlights of the wide bands of gold that frame the space suggesting the glittering surfaces of mosaics, perhaps why it recalled the splendor of Venice to 19th-century viewers. As the eye descends and takes in trefoil arches of the chancel and transepts and the four massive piers which support the tower, the contrast of color shifts to deeper tones of the complementary colors, red and green to match and enliven the more subdued light of these spaces. Although these color schemes may reflect La Farge’s impressions of the churches that he had seen in his trip to Europe in 1873, the use of complementary color combinations was also the result of his earlier inquiries into the scientific aspects of light and color.

La Farge acknowledged that the color theories of the chemist for the dyeworks of Gobelins tapestries, M. E. Chevreul, had the most profound impact on his work and especially on his design of stained glass. ( Cortissoz, p. 88). Chevreul’s treatise, The Laws of the Simultaneous Contrast of Colors, a version with illustrations was first printed in 1839 and reprinted in several languages and formats into the late 1860s. (Gage, p. 173) What was new in Chevreul’s theory was the realization that the perception of differences in hue and value of a color depended as much on the colors placed next to it as it did to the actual chemical composition of the pigment or dye itself. Chevreul advocated using pairs of complementary colors to intensify the vibrancy of each color in the pair. His book also outlined the application of these laws to the various decorative arts from to murals, mosaics and stained glass. Chevreul noted, for example, that mural paintings, which were not seen close up by the viewer could be painted predominantly in contrasting flat tints or tones with only minimal shading to indicate figural form and gesture. A suggestion that La Farge followed for the figures at Trinity describing both the monumental figures of the tower and those in the narrative scenes with loose brushstrokes that implied sculptural form without great contrast of light and dark.

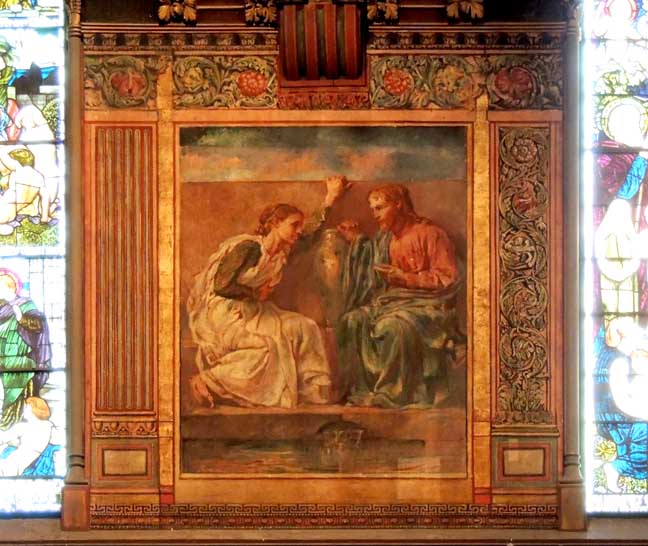

Unlike the monumental figures of the tower, however, that stand out against a background of a solid or flat color, the narrative scenes involve figures in a particular setting. One of the artistic problems that intrigued La Farge was how to describe the nuances of direct and reflected light on figures and their surroundings as they appeared in real life. This artistic question led to his admiration for the Barbizon School painters whose landscapes and paintings of people of the countryside had a directness of description and color that was contrary to what La Farge saw as the “tricks” of academic paintings. In a lecture on the Barbizon school , La Farge’s description of the sky of a landscape by Rousseau could equally describe the sky in La Farge’s painting, Christ and the Woman of Samaria. His description also reveals how he synthesized Chevreul’s theories with what he observed and appreciated in Japanese prints.

“ He is known to have absolutely painted in a new way works which were already among the most remarkable studies of Nature that modern art had given…One case that I recall was caused by his sudden introduction to the question brought up by the ordinary little Japanese prints that you know, the extreme luminosity obtained by a few flat, clear colours, and by their relation one to another so that the mere quality of tone and its belonging to one or the other of what we call divisions of what we call colour, that is to say a red placed in a sky of a certain value, not too deep, is forced at once into the background and into being a sky by a certain blue which comes against it. There is nothing concealed or involved--anybody can see it as it were--There is no trick in it. It is a scientific statement. There it is. Somehow or other you see that the pink sky involves the opposition of blue as a perpendicular against it, and the thing is solved with no modeling, or modelling so slight that it is not worth speaking of, and there it is. ….. Would it be possible to paint with that simplicity in his material oil? Would it be possible to use these evident secrets?..... The later painters, as you know, immediately afterward began to take up questions of a similar kind, and since then up to the present movement we have had the struggle to represent light by colours, by an arrangement of colours, an opposition of colours, a concatenation of colour. (La Farge, pp.137-38)

The luminosity of the scene at the well is the result of La Farge’s attempt to translate what he observed in nature, in other paintings, and what he knew about the interaction of colors. To communicate the style of these effects to his assistants he often used watercolor sketches, such as the watercolor study made for an angel for the tower, now in the Yale Art Gallery. ( Illustration 2 ) In the sketch, one sees the complementary color harmonies of dark reds against greens and the orange tones of the robe contrast with the cobalt blue sky, all of it heightened by the sparkle of a light mauve and the white highlights of the watercolor paper. ( Note --- A large watercolor modello for the figure of Isaiah is in a private collection, Henry A. LaFarge, p.37. For the later Purity window La Farge made an encaustic modello now at Vareika Fine Arts , Newport. )

Another exceptional aspect of La Farge’s design of the interior admired by 19th-century critics was the way in which the decorative detail enhanced and defined the architecture. In fact, La Farge remarked in a lecture to young aspiring architecture students in 1892, that the architect was just beginning to think of the artist in painting as a helper in his scheme. (Waern, p. 33) He pointed out to them that they should think of colour not as a mere pleasing arrangement of tones, but as means of construction, since color could suggest hard or soft stone surfaces; and the different values of color could suggest sculptural mouldings. He mentions as an example his work at Trinity, where his decoration for the nave walls continued into the gallery above the west end. He had done this to give the impression of greater length, since this arm of the Greek cross plan, had been shortened by the inclusion of a narthex. Another aspect of the nave architecture that he must have considered as one of the “deficiencies” was the placement of the two windows in the clerestory, which divided the wall into areas of different dimensions -- hardly ideal for composing a series of narrative scenes. (Waern, p. 35-37) (Illustration 3)

A preliminary pen and ink drawing of the north wall of the nave, dated December/October 1876, shows how La Farge began to solve this problem. (Illustration 4) The core of the design is the section of the wall between the two windows with the narrative panel, Christ and the Woman of Samaria. Here he sketches in a wide frame based on the dimensions of the sculpted architectural features of a corbel and small brackets above the center of the panel, and the vertical lines of the vaulting above the side windows. By continuing the horizontal and vertical lines in each section of the wall he creates a harmony of rectangular shapes. In the small section next to the massive central pier he places a pair of colonettes that are of the same scale as the colonettes of the nave arcade below and echo the capitals of the colonettes of pier. Within the border of the narrative scene he indicates Roman acanthus scrollwork for the top, bottom and right side suggesting a completed frame, but on the left side he indicates a fluted pilaster, which in the completed decoration matches a similar fluted pilaster to frame the window on the left. Thus, his solution utilizes an asymmetrical arrangement of pattern within an underlying grid to imply connections between the different architectural forms. His early drawing also shows faint pencil lines of large architectural scrolls as possible ideas for the west end of the nave wall in the gallery. La Farge’s biographers note that the nave decoration, which did continue along the north wall into the western gallery, was covered when the two organs were installed in the corners of the west end. (Cortissoz, p.157 and Waern, p. 37 )

The incredible variety of pattern throughout the building reflects La Farge’s aesthetic taste and “his belief that art is the love of certain balanced proportions, which the mind likes to discover.” ( Katz, p. 115) A similar belief that there were principles of universal harmony underlying simple patterns was shared by Owen Jones, whose handbook, The Grammar of Ornament, first published in 1856 sets forth principles of design in architectural ornament based on analysis of historical examples from different cultures. Illustrated with color lithograph plates, it is likely, that this book was the source for much of the ornament at Trinity, such as the Roman acanthus scroll work that frames the narrative panels or the Renaissance designs in the gilded vaults above the windows . (Illustration 5)

Although two narrative panels had been planned for the nave from the initial contract, at the time of the consecration of the church on February 9, 1877, the walls of nave were just a light red with gilded ornamentation around the windows. On February 27 of that year La Farge writes to building committee member, Charles Parker, about the details of completing the decoration on the nave walls. Although La Farge mentions some options for more ornamentation in the spandrels of the nave arcade as seen on the ink drawing now in the National Gallery of Art, he does not want to commit to more decorative pattern until he could see the effect of the two completed paintings. The decoration should be subordinate to the narrative paintings. The total visual effect of the interior, then, was a priority at each phase of the project. (Weinberg, pp.346-47) Documents indicate that by early March the drawings were ready and that the assistants could begin transferring the cartoon to the north wall. This painting was completed by October 1877, although La Farge was also working on murals for St. Thomas Church in New York. The painting on the south wall was completed later, sometime after February 1878 and before May 1879. ( Weinberg ,pp. 348-349)

The subjects of the nave wall paintings, Christ and the Woman of Samaria and Christ and Nicodemus, had been suggested by Phillips Brooks. As mentioned in an article in the New York Herald, la Farge stated that these were subjects that interested him. (Weinberg, referencing Cortissoz Corrspondance p. 109) Narrative subjects had been the focus of the illustrations he produced in the 1860s; and he often used a biographical narrative in his approach in his articles on Old Master paintings published in McClure’s Magazine. (Katz, 107). And, La Farge included Christ’s encounter with the woman of Samaria in his later book, The Gospel Story in Art.

References to the Samaritan woman and especially Nicodemus, however, were frequent in Brooks’ sermons. They might be mentioned briefly as in his 1875 sermon on the “Gifts of God,” to show how Christ gives of himself, whether offering living water to the Samaritan woman or knowledge to Nicodemus. Or the words spoken by Christ in these encounters might be the focus of the whole sermon, as in the sermon of October 1875, which focused on the meaning of Christ’s saying to Nicodemus that “Except a man be born again, he cannot see the kingdom of God”. In Life and Letters of Phillips Brooks, vol. II, Alexander V. G. Allen writes that one of Brooks most impressive sermons was on Christ’s words to the Samaritan woman, “the hour cometh …..when the true worshippers will worship the Father in spirit and in truth.” To such a moment Phillips Brooks looked as the completion and glory of the Christian church. ( Allen, p. 846)

An indication of Brook’s analysis of the person of Nicodemus can be gathered from several sermons. In the sermon, “Deep Calling into Deep” (Light of the World and Other Sermons pp. 251-252. ) Brooks says of Christ, “Men came to Him with selfish little questions about the division of inheritances, and He would not waste His time on them; but Nicodemus came eager for spiritual light, and Christ would sit all night and teach him….. In two of his sermons preached in English churches, Brooks also analyses Nicodemus’ connection to orthodox Judaism. In one sermon, “Gamaliel” he characterizes both Nicodemus and Joseph of Arimathea as belonging to the School of Hillel, the more liberal of the two groups of orthodox Jews at that time. In another sermon, “Nature and Circumstances,” however, Brooks points out the limitations of Nicodemus’ orthodoxy. “ Nicodemus wanted Christ to meet him in a lower world, a world of moral precepts and Hebrew traditions where the Pharisee was thoroughly at home, but Christ said “No, there is a higher world, you must go up there; you must enter into that; you must have a new birth and live a new life,--in a life where God is loved and known and trusted and communed with.” ( Sermons Preached in English Churches, p. 246, and p. 211) In yet another sermon, “Great Deeds of Christ,” Brooks interprets the impact of the encounter with Christ, “Nicodemus came to him, and the creed-bound Pharisee became the faith-clad man.” (The Spiritual Man and other Sermons, p. 308)

Since there are no documents relating to conversations between the artist and rector about the themes of these biblical narratives, it is difficult to know how specific Phillips Brooks instructions might have been to John La Farge. The paintings themselves, however, show several correspondences. In the panel of Christ and the Samaritan Woman, La Farge highlights Brooks’ emphasis on Christ’s gifts of living water and instruction; and in the panel Christ and Nicodemus La Farge emphasizes Brooks’ characterization of Nicodemus as an orthodox Jewish elder and Christ’s challenge to Nicodemus to engage in a new and deeper spiritual life.

From his experience creating literary illustrations, La Farge was aware of different narrative strategies. When La Farge discussed a painting of Christ and the Samaritan woman by the Baroque artist, Philippe De Champaigne, in The Gospel Story in Art, he observes that the artist “follows the classical French teaching and tradition of meeting all the points of the story.” (Illustration 6 ) Using the language of gesture, De Champaigne shows the Samaritan woman “as both accepting and rejecting Christ’s statements; and of being astonished and yet not inimical.” The Baroque composition sums up the different moments of the conversation. She is standing, as if she just arrived. Her gaze is toward Christ and her expression shows that she is absorbed in what she is hearing. Her right hand is elegantly placed on her heart, but the left arm is extended away from Christ and her hand flexed up in a gesture of surprise. Although her torso faces Christ, her left foot is stepping away. Her water jug left at the side of the well as she prepares to tell the people of the town what she has learned.

La Farge, however, takes a different approach. He emphasizes the crucial moment of the encounter, when the woman understands who Christ is and his gift of living water. The water jug with its glistening highlights is in the center of the painting. Christ is seated to the right. He is speaking to the woman and raises his left hand in a gesture of instruction. His right hand holds the rim of the water jar; and from a culvert below the fountain flows a spring of running water. The Samaritan woman does not question Christ in her gestures or expression. Her whole figure inclines towards Christ; and with her left hand braced at the top of the fountain wall, she raises her right hand to her breast. Nor is she completely settled on the well, but she bends her right leg as if to kneel before Christ. (Illustration 7)

While this scene at a wall fountain has the look of the 19th-century Barbizon school’s depiction of country life---not only the village setting, but the brushwork used to describe the faces also shows the influence of La Farge’s mentor, William Hunt, who was a student of the Barbizon painter Millet---there is something in the geometrical order of the composition and hierarchy of the gestures that is medieval; something in the graceful outline of figures and drapery that echoes the Italian Renaissance. In fact, the overall composition is based on Gothic representations of the coronation of the Virgin, while certain gestures and the drapery are derived from works by Raphael.

The eclecticism of La Farge’s style has been frequently noted. The art critic, Frank Jewett Mather, Jr. offered an explanation in his comment, that for La Farge the great art of old was like a second Nature, with an equally great reservoir of forms, from which La Farge could find a motif that served his needs. (Mather, p.245) La Farge also, seems to be justifying his practice of “borrowing” motifs from other works of art when he discusses Raphael’s assimilation of the styles of his master, Perugino, and of Leonardo and Michelangelo.

“In those days, as in the Japan of today, the work of the master was not only the example, but the model and the storehouse of the pupil. He borrowed this or that scheme and filled in with fragments of his own; or he imitated fragments to put into his own new scheme. And so every one borrowed one from the other; it not being an injury but a manner of admiration…..”

La Farge points out further that Raphael internalized the method or motif to such a degree that his borrowing developed the underlying idea of the motif taking it to another level or artistic possibility, thus creating something original.

“It must also be said that he made all his own, that it was rather a renewal of himself, than an accumulation of knowledge which defines this continuous increase in the wealth of his resources…and never does he seem more original than in the ideas that he borrows. He seems to show to what further use the concealed life of the thing he admires can be turned…(LF, Great Masters, pp. 74, 76, 77)

La Farge believed that an artist’s work reflected their personal way of seeing, which was determined by their unique accumulation of memories and associations. In studying from master works, then, one should look beneath the surface appearance of the work, and try to understand the process of the intended preserved and rejected memories of the artist, this will enable the student to assimilate the not only the ideas and forms, but even the technique or gesture of the artist’s hand. (Katz, p.110-111)

Not surprisingly, La Farge used this same process of combining visual memories and associations in composing narrative scenes. La Farge indicates the literary source for the figural composition of Christ and the Woman of Samaria, when recounts the narrative in The Gospel Story in Art. “As our Lord crossed this land of Samaria He stopped at the gates of a town called Sychar, feeling weary. (St. Augustine tells us that His journey in the form of the flesh was taken to meet humanity.)” (La Farge, p. 194 ) This interpretation of the reason for Christ’s journey mentioned by La Farge is found in the homily or sermon that St. Augustine wrote on the encounter of Christ and the Samaritan woman (St. John 4: 4-42). Phillips Brooks may have mentioned this homily to him, but given La Farge’s Catholic school education and his wide literary and philosophical interests, it is not surprising that La Farge consulted the homily for a further understanding of the significance of the encounter. In early medieval fashion, St. Augustine’s verse by verse commentary of the biblical text explains both its literal and allegorical meanings. St. Augustine interprets the Samaritan woman as a type or symbol of the Church, who still needs to be justified by faith. It is through her questions and Christ’s responses that she is brought from ignorance into spiritual understanding.

In terms of visual associations for the relationship between Christ and his Church, La Farge’s composition suggests that he recalled the images of Christ’s coronation of the Virgin on Gothic cathedrals. In these portal sculptures the Virgin is seated on a throne next to Christ and is receiving a crown either from Christ or from an angel. In these images the Virgin is portrayed as both the Queen of Heaven and as the Church, the Bride of Christ. ( Katzenellenbogen, pp.59-61) La Farge surely had seen a variety of these sculptures on his 1873 trip to France to look at stained glass, but the kneeling position of the Samaritan woman suggests that an image from the Cathedral of Santa Maria de la Regla, Leon provided the model. (Illustration 8) According to his biographer, Royal Cortissoz, La Farge mentioned that he had a special collection of photographs of Spanish Romanesque churches, Avila and so forth that had been made for Queen Victoria during her visit to Spain. (p. 154) La Farge had brought the photographs to Richardson in regard to possible design solutions for the tower of Trinity church. Two albums of photographs entitled, Souvenirs from Spain, now in the Royal Collection, are catalogued as part of the archives of Prince Albert’s photograph collection. These albums include images of Salamanca Cathedral, on which Trinity’s central tower is based, and images of the Cathedral of Santa Maria de la Regla, Leon and other Gothic churches.

To give a greater naturalism to the scene, however, La Farge modified the frontal pose and drapery of Christ on the Gothic portal using a painting of the “Coronation of the Virgin” by Raphael, which he had discussed in his book, Great Masters, (p.74). (Illustration 9) The heartfelt gesture of the Samaritan woman was probably borrowed from a drawing by Raphael for one of the Three Graces for the Villa Farnesina (Illustration 10). The gesture of the Samaritan woman’s raised left hand placed at the top of the wall to steady herself may reflect La Farge’s memory of a painting by William Morris Hunt, “Woman at a Fountain”, 1852-54 now in the Metropolitan Museum in New York. (Illustration 11 ) And, the idea of a wall fountain, rather than the typical draw well, may be from his memories of the 1857 visit to his relatives in St. Pol-de-Leon, where he made a drawing of a wall fountain in the village. (Illustration 12) Following the practice of Renaissance artists, La Farge fuses his visual memories of places, monuments, and texts to create his unique portrayal of the narrative.

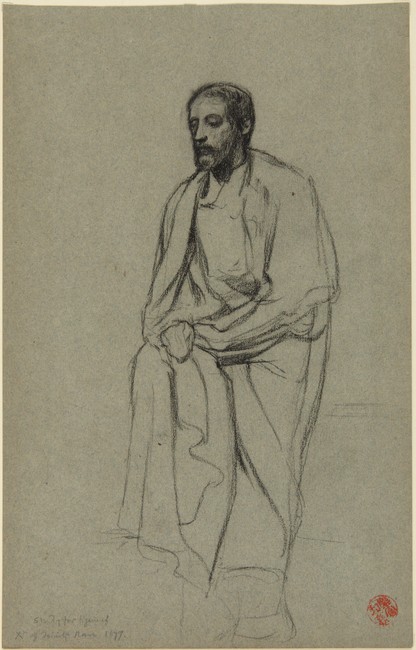

For the painting of Christ and Nicodemus, La Farge followed the same process of “building a picture” from a combination of studies from nature and from “a certain reaching out of the hands back to greater art of the past” (Higher Life, p.146 ) . La Farge’s painting of this scene was widely admired; and it was reproduced as a Copley print by Curtis and Cameron in 1896 as part of their prints of notable works of art. ( King, p. 19) Engravings of the drawing were also published in the popular press. ( Humphries, 1883, p.12 and Seaton-Schmidt, 1910, p.180) (Illustration 13). Augustus Saint-Gaudens writes to La Farge from Paris on December 29, 1879,

“…I first wish to write to you about your drawing of “Christ and Nicodemus” that I saw in Harper’s sometime ago---I was really stirred by it, and as I had just returned from Italy I was all the more impressed.” (p. 267). Saint-Gaudens’ praise implies a comparison with the famous mural paintings of the Italian Renaissance. Others have also remarked on the “allusions to traditional sources of monumental figures” (Weinberg, p. 350). In her 1902 study of American Mural Painting, Pauline King highlighted the composition and the mood of the painting. (pp.27-29).

“ Simplicity of composition is one of the charms of Mr. La Farge’s work. He presents the events of the Old or New Testament in so natural a way ……The sentiment of repose, so pleasantly conveyed in the quiet scene, the arrangement of light, which brings out exquisite gleams of brightness upon a rich depth of tone, and the interesting character of the heads combine to make this canvas one which dwell long in the memory.”

La Farge sets the scene in a loggia against an evening sky of fading light. (Illustration 14) Nicodemus, grey-haired and bearded, sits on a low bench, his head and body draped in a heavy red cloak. He rests his back against the loggia wall, while Christ stands to the right facing him. Christ has placed his right foot on the edge of the bench and leans forward to listen with his crossed hands resting on his raised knee. Nicodemus points with his left hand to a passage on a scroll spread across his knees. He holds his right hand to his breast slightly turned as if to make a comment or ask a question. Christ does not return Nicodemus’ gaze, but appears lost in thought.

The choice to represent Christ standing is unusual in paintings or prints of this scene. Even, Brooks, in his sermon, imagined Christ sitting all night talking with Nicodemus. The way Christ places his foot on the low bench so that he can rest his hands on his raised knee suggests both repose and the reflection of a philosopher. The inspiration for this composition is likely the monumental frescoes by Raphael in the Chigi Chapel in Santa Maria della Pace in Rome. On the upper wall on either side of a small arched window are pairs of prophets: Hosea and Jonah on the left; and David and Daniel on the right. In each pair, one is seated and one is standing. (Illustration 15)

Although La Farge passed up the opportunity to visit Italy with his relative, Paul de St. Victor, and Charles Le Blanc in 1857, ( preferring to go to Dresden and other cities of Northern Europe) , images of Italian art and architecture were available in engravings and the new chromolithographs, such as those published by the Arundel Society. In fact, La Farge owned the Arundel Society’s complete set of Giotto’s frescoes in the Arena Chapel, Padua. Drawings for the prophets Hosea and Jonah were reproduced in prints published by Conrad Metz (in reverse), and there is a photograph of the drawing in Prince Albert’s collection of works after Raphael. (Illustrations 16 and 17 )

Raphael’s figures of Jonah and Hosea show, indeed, how he did not borrow, but transformed the visual ideas of other artists, in this case Michelangelo’s figures for the Tomb of Julius II. The figure of Jonah uses the idea of a figure resting one foot on a small block that Michelangelo had used in the Captives to create a spiral movement in a standing figure. The animation of this pose was used not only by Raphael in the figure of one of the philosophers in the School of Athens, but also by other artists. Andrea del Sarto, for example, reversed the pose for the figure of the Evangelist John in his Madonna of the Harpies altarpiece. ( Illustrations 18 and 19 )

In the nave panel, La Farge uses the low bench rather than a block to support Christ’s foot. He also adjusted the animated position of the arms and torso of these Renaissance figures, perhaps because they conveyed the intention of exhortation or instruction, which did not correspond to Christ’s incisive, yet enigmatic statements to Nicodemus about kingdom of God. A drawing now in the Princeton University Art Museum, shows a study for the figure that La Farge made using a model from life. (Illustration 20 ) In the drawing, La Farge focuses his attention on the expression of Christ’s face and just indicates the general outline the shoulders, relaxed arms, and hands. The pencil inscription indicates that it is a study for the figure of Christ, and gives the date, 1877. He must have liked the drawing, since he later authenticated it with the red monogram seal, which he had specially commissioned during his visit to Japan in 1886. In the nave painting, La Farge changes the position of Christ’s head to turn more directly towards Nicodemus.

While the figure of Nicodemus shares with Raphael’s Hosea the seated position and wide head-covering mantle of the prophet, La Farge does not adopt the direct frontal pose of Hosea as he points to his upright tablet. Nor does he use the elaborate design of the drapery over the knee, which Raphael developed from Michelangelo’s Moses. Instead, La Farge chose to develop the pose of one of the prophets just above the lintel of the Virgin or south portal of the façade of Amiens cathedral. (Illustration 21) These figures tilt their heads and point to passages on the scrolls unfurled across their knees. Two of the prophets also place one hand over their heart. (Illustration 22) In the center of this row of prophets is an image of the ark of the covenant flanked on one side by Moses and by Aaron on the other. These high relief sculptures symbolize the Old Testament law, priesthood, and the prophets. (Katzenellenbogen, p.61) They visually support the images of the enthroned Christ and Virgin in the tympanum. By association, La Farge uses the image of a prophet and Hebrew text to emphasize Nicodemus’ adherence to orthodox belief. While Nicodemus looks up at Christ as he points to a passage from the scroll, Christ does not respond with an expression of agreement, but has a look of reserve, as though something more is needed. Again, La Farge chooses to represent a critical moment of the encounter and the main points of Brooks’ sermons.

La Farge unites these two scenes on opposite walls of the nave by mirroring the elaborate frames, and by a common backdrop of stone architecture against a blue sky with tinted clouds reminiscent of Venetian painting. (This is also the backdrop of the lunette with St. James in the transept.) Further uniting the decoration is adjustment of the color in the panels to the dominant red-orange of the tower following Chevreul’s principles. His choice of the encaustic medium enhances the tones of the absorbed or refracted light on the figures; and the loose brushwork reveals the presence of the artists’ hand throughout the decoration.

Bibliography

Allen, Alexander Viets Griswold, Life and Letters of Phillips Brooks, vol. 2, London: Macmillan and Co.,

1900

Augustine, S., Bishop of Hippo, Homilies on the Gospel according to St. John, and his First Epistle,

translated with Notes and Indices, Vol. 1, Oxford: John Henry Parker, and London, F. and J. Rivington,

1848. Preface and translation by Rev. H. Browne, M.A. of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge

Brooks, Phillips, New Starts in Life and other Sermon,s eighth series, New York: E. P. Dutton, 1910

The Gifts of God, May 1875, “The New Birth”---John III, 3 “Except a man be born again, he cannot see

the kingdom of God, ” October 1875

-----Sermons Preached in English Churches (1883 original copyright) Third series, New York: Dutton,

1910, “Nature and Circumstances,” “ Gamaliel”

-----Light of the World and Other Sermons, (1890 original copyright) New York: E.P. Dutton , Fifth series,

1902, “Deep Calling into Deep”

-----The Spiritual Man and other Sermons, by Phillips Brooks, Rector of Trinity Church Boston, 3rd

edition, London, [published ]R. D. Dickenson, 1895, “Great Deeds of Christ”

Chevreul, M. E., The Laws of Contrast of Colour: and their application to the arts of ……Translated from

the French by John Spanton, London: Routledge et. al. , 1857

Cortissoz, Royal, John La Farge: a Memoir and a Study, Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1911

Crowninshield, Frederic, Mural Painting, Boston: Ticknor and Company, 1887

Curran, Kathleen, “The Romanesque Revival, Mural Painting and Protestant Patronage in America,” The Art Bulletin, Vol. 81, No. 4 ( Dec., 1999), pp. 693-722.

Gage, John, Color and Culture: Practice and Meaning from Antiquity to Abstraction, Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1993.

Hansen, Harold J. “The Development of New Vehicle Recipes for Encaustic Paints”, Leonardo, Vol. 10,

No. 1 (Winter 1977), pp. 1-5.

Humphries, Mary Gay, “John La Farge, Artist and Decorator,” The Art Amateur 9 (June, 1883), pp. 12-

14.

Jones, Owen. The Grammar of Ornament, London: Day and Son, Lithographers to the Queen, 1856

Katz, Ruth Berenson, “John La Farge, Art Critic,” The Art Bulletin, vol. 33, No. 2 (June, 1951), pp. 105-

118.

Katzenellenbogen, Adolf, The Sculptural Programs of Chartres Cathedral: Christ, Mary, Ecclesia, New

York: Norton Library, 1964, original copyright 1959, John Hopkins Press

Pauline King, American Mural Painting: A Study of the Important Decorations by Distinguished Artists in

the United States, Boston: Noyes, Platt and Company, 1902

La Farge, Henry A., “The Early Drawings of John La Farge,” The American Art Journal, Vol. 16,

No.2 (Spring, 1984) pp. 4-38.

La Farge, John, Great Masters, New York: McClure, Phillips, and Co., 1903.

-----, The Higher Life in Art, Scammon Lectures, at the Art Institute of Chicago, 1903

-----, The Gospel Story in Art, New York: The Macmillan company, 1913

Mather, Frank Jewett, Jr “John La Farge--An Appreciation” from World’s Work, vol.21 (1911)

Essay also in Estimates of Art by F. J. Mather, Jr.- 1916--Chapter X.

Metz, C. M., Imitations of ancient and modern drawings from the restoration of the arts in Italy to the

present time together with a chronological account of the artists and Strictures on their works in

English and French …. London, 1798

The Reminiscences of Augustus Saint-Gaudens, Vol. 1, edited and amplified by Homer Saint-Gaudens,

New York: Century Company, 1913

Richardson, H. H. “Description of the Church edifice” in Consecration Services of Trinity Church Boston,

February 9, 1877 with consecration Sermon by Rev. A. H. Vinton, D.D.; an Historical Sermon by Rev.

Phillips Brooks, and a Description of the Church edifice by H.H. Richardson, Architect. Boston: printed

by order of the Vestry, 1877

Seaton-Schmidt, Anna, “John La Farge: An Appreciation,” Art and Progress, Vol. 1, No. 7, (May, 1910)

pp. 179-184.

Waern, Cecilia , John La Farge: Artist and Writer, London: Seeley and Company Limited, and New York:

Macmillan and Co. , 1896

Weinberg, Helene Barbara, “ John La Farge and the Decoration of Trinity Church, Boston”

Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, Vol. 33, No.4 (Dec., 1974), pp. 323-353

-----, “The Career of Francis Davis Millet,”Archives of American Art Journal, Vol. 17, No. 1 (1977) pp. 2-18

Yarnall, James L., “John La Farge’s ‘Portrait of the Painter’ and the use of Photography in His Work,”

The American Art Journal, Vol. 18, No.1 (Winter, 1986), pp. 4-20

-----, “Adventures of a Young Antiquarian: John La Farge’s ‘Wanderjahr’ in Europe, 1856-57,” American

Art Journal, Vol. 30, No. 1 / 2 (1999), pp. 102-132

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- July 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- October 2013

- September 2013

At "Educational Forums," enrich your spiritual journey by exploring our resources including videos of lectures, essays by priests, and other pieces about our faith, our church, and what it means to be a disciple of Jesus in the 21st century.

Comments